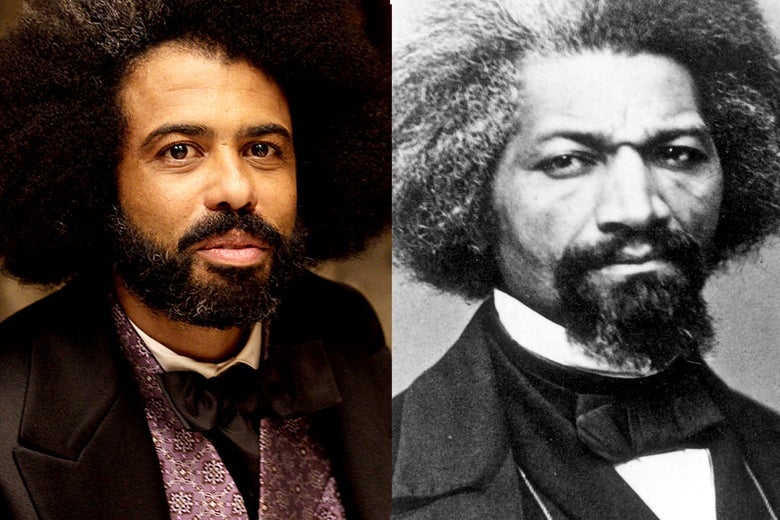

Viewers of the Showtime series The Good Lord Bird, adapted from James McBride’s 2013 novel of the same name, got a real taste of its commitment to irreverence toward treasured bits of American history upon watching the third episode on Sunday night. In “Mister Fred,” John Brown (Ethan Hawke) and Henry (Joshua Caleb Johnson) go to visit Frederick Douglass at his home in Rochester, New York. This is a familiar move in historical entertainment: If you sign up to watch a biographical series, you expect to see a new actor stride into frame and introduce himself as Napoleon every once in a while. But in this case, the abolitionist hero—played by Hamilton’s Daveed Diggs—seems like anything but.

As played by Diggs, the acclaimed orator makes broad, hammy gestures as he delivers a speech to an adoring audience full of fainting white women. When he meets the travelers, he mocks Henry’s uneducated ways of speaking, cutting him down for addressing him as “Fred.” (“Do you know you are not speaking to a pork chop but rather a fairly considerable and incorrigible piece of the American Negro diaspora?” Diggs bristles.) The “King of the Negroes,” as Brown calls Douglass, naysays the Old Man’s ideas for armed rebellion even as he writes glorious speeches in his safe, Northern Victorian mansion. And, last but not least, Douglass is living with two women: his wife, Anna, who is Black, and his white mistress, Ottilie Assing. (“He’s a king. They do their own rules,” Brown mutters to Henry after awkwardly introducing Ottilie.)

If it made you feel strange to see Frederick Douglass treated this way, that was probably on purpose. “We had fun with the Frederick Douglass character,” McBride told the New York Times recently. “We don’t mean any disrespect to him and to the many thousands of historians who revere him and then the millions of people who revere his memory. But his life was rife for caricature.” For a writer of historical fiction interested in whatever awkward, messy, human drama can be found inside John Brown’s story, a Frederick Douglass sequence is an opportunity not to be missed.

The Douglass love triangle offers the most fertile ground for comedy. Assing, a German journalist who met Douglass in 1856, had a 24-year relationship with him, often living in his Rochester house . We don’t have confirmation that this relationship was sexual (though the show assumes that it was), but like the Ottilie of The Good Lord Bird, played with flushed fervor by Lex King, the historical Assing worshipped Douglass. In his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Douglass, historian David Blight describes the freethinking feminist’s attraction to the man: “As a German romantic, she was always in search of the hero in history, the maker of new nations, new ideas, and new times.” It seems that when she found Douglass, Assing latched on—permanently. Blight concludes that the two “were probably lovers.”

Assing and Douglass’ relationship, based in words, books, and ideals, stood in contrast to his marriage with Anna. Anna Murray-Douglass was a homemaker and maternal figure par excellence. She had helped Douglass out of slavery, born him five children in 10 years, and had her own strong abolitionist ideals, but she was “largely illiterate,” in Blight’s words, and seems to have had little interest in participating in the world outside her home. Assing “held Anna in utter contempt,” Blight writes, and hoped that at some point, the two would divorce and Assing would be able to step in as the new Mrs. Douglass. This never happened, and Assing died by suicide in 1884, after learning that Douglass had just remarried another, younger woman. (Anna had died two years prior.) This triangle between Anna, Frederick, and Ottilie was the subject of a 2003 novel by Jewell Parker Rhodes, called Douglass’ Women, as well as a book by Maria Diedrich about Assing and Douglass’ relationship, called Love Across Color Lines, based on some of their correspondence.

The Good Lord Bird, television version, contrasts Anna’s warm reception of Brown—she hugs him when they meet, saying to Frederick, “How dare you forget to tell me that my favorite John Brown was paying a visit? We need to get some soap on that skin and some meat on those bones”—with Ottilie’s fear of, and rejection of, the Captain. After Douglass and Brown fight at the dinner table, Ottilie hisses at Brown—“You are the craziest person who ever sat at this table!” She thinks Brown will get Douglass killed, while Anna is on Brown’s side, telling Douglass, “Blood must be spilled. You know it. I know it.” The choice to center the Douglass episode around the two women makes for a lot of broad comedy, but it also gives the show a chance to explore Douglass’ own mixed feelings about what Brown was planning to do.

What about the fanciness of Douglass’ house, which stands in stark contrast to the comfortless life we’ve seen Brown and Henry living? At the Douglass’ dinner table, where the assembled group eats turtle soup in leisure, Hawke’s Brown—who starts the meal by combing his mustache with a fork—tells the assembled group about the way his men were living in Kansas: “We were eating nuts in the rain,” he says. “It just makes us more fervent for the cause.” In a 2013 interview with NPR, McBride said he had the novel’s narrator Henry call Douglass “a speeching parlor man” to show how different Brown and his crew were from other abolitionists. “Frederick Douglass was a man who made speeches,” McBride said. “Henry was a kid who had been out on the plains and firing weapons and getting drunk … the abolitionists were not like the rugged people out West, and they were not like John Brown either. They were people who made speeches and did politics.” This doesn’t seem entirely fair, since Douglass was a member of the Underground Railroad and sometimes did perform feats of derring-do. After the so-called Christiana Riot of 1851, in which four fugitives and their defenders killed a slaveholder from Maryland who had come to Pennsylvania to try to recover them, Douglass personally took some of the highly sought-after runaways from his house to the ship that would take them to Canada.

But it’s true that Douglass’ primary weapon was his presence—his voice, his face, his words. In this episode, when Henry first beholds Douglass, who’s lecturing the crowd in Rochester, the boy says in voiceover: “I never knew a Negro could speak like that, or look like that. He was downright beautiful. I never thought I would say that about a gentleman, but he sure was a sight. I couldn’t tear away. Nor could the whites.” This compelling quality was something that Douglass consciously cultivated: For decades, he posed for portraits as a political act, hoping to force Americans to contemplate the dignity of a distinguished, self-possessed Black man. But as Blight points out, while in the 1850s the historical Douglass’ “public image was of a virile man of the world, holding audiences in rapt control with words as well as charisma,” behind the scenes, he was frequently ill, broken-down, and overworked. He was stressed about money, and he went on breakneck speaking tours to raise funds to support his newspaper and his family. The production of Douglass, the public figure, wasn’t easy.

And what about the supposed “betrayal” foreshadowed in the episode? In voiceover, during a scene in which Henry and Douglass drink in his study, Henry muses that if he’d known at the time what he knew later, he might have taken his derringer and shot Douglass then and there. “He would short the Old Man something terrible,” Henry says, “at a time when the Old Man needed him most.” In this, he echoes the mixed way the world reacted to the historical Douglass after the Harper’s Ferry raid, when it became clear that Douglass had been asked to participate personally and had refused. One of Brown’s men, John Cook, who had been captured, accused Douglass of having said he would go along with the raid and then going back on his promise. All this while Douglass was forced to flee the country ahead of federal authorities, who tried to arrest him as an accessory.

Yet it seems that the difference between the two was a difference of opinion on strategy, not method. Douglass was not afraid to call for blood. As Blight points out, during the 1850s, Douglass did not hesitate to applaud the killing of slavecatchers who came to free states to retrieve Black people who had fled slavery. “Every slaveholder who meets a bloody … is an argument in favor of the manhood of our race,” were Douglass’ words. Blight believes that when Douglass came to meet Brown in southern Pennsylvania, the very last time they saw each other, Douglass declined to participate in the raid because he simply wasn’t ready to “die in such futility.” Blight points to the very fact that Douglass came to meet Brown in such a risky location as demonstrating “a kind of desperate loyalty.” And, in later years, though Douglass continued to say that he didn’t think the raid had been a good idea, he was always publicly supportive of Brown himself. In 1881, in a speech in honor of Brown, Douglass said this:

His zeal in the cause of my race was far greater than mine—it was as the burning sun to my taper light—mine was bounded by time, his stretched away to the boundless shores of eternity. I could live for the slave, but he could die for him.

Parts of upcoming episodes of The Good Lord Bird are a bit kinder to Douglass—though Henry, in voiceover, does not forgive. And this is, after all, Henry’s tale, told largely from his point of view. It makes sense that as this young man struggles to choose between the humble, strange John Brown, who asks him to risk death, and the proud, powerful Frederick Douglass, who symbolizes freedom and a withdrawal from the fight, the story would take every opportunity to present the contrast as a stark one.

"bird" - Google News

October 20, 2020 at 06:22AM

https://ift.tt/2INzY39

Why The Good Lord Bird Makes Frederick Douglass Look Like a Jerk - Slate

"bird" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2s1zYEq

https://ift.tt/3dbExxU

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Why The Good Lord Bird Makes Frederick Douglass Look Like a Jerk - Slate"

Post a Comment