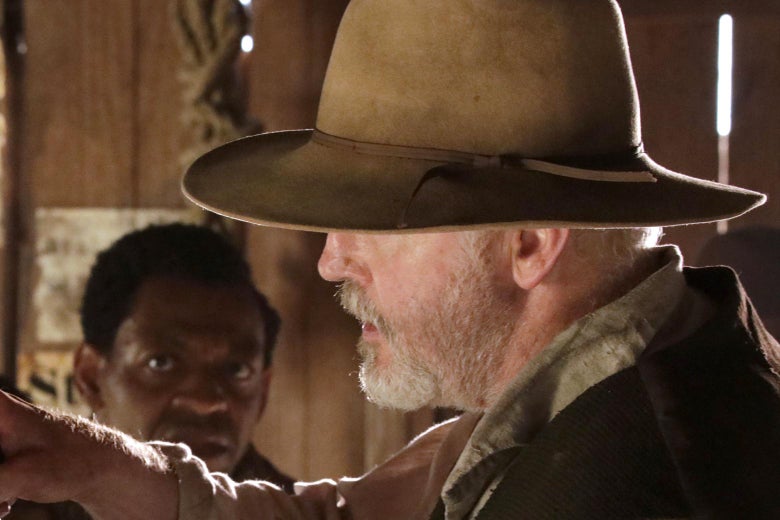

The Good Lord Bird, the Showtime series adapted from the 2013 National Book Award–winning novel by James McBride, is the first time since 1955 that we’ve seen a version of the John Brown story appear on screen. Ethan Hawke, who plays the heck out of Brown as a craggy, eccentric old crusader, has said that in his preparation for the role, he imagined the Old Man as “a giant elk, walking through the forest”—a person of singular gravitas. But McBride’s story is also a coming-of-age tale, and for a historical tragedy, it’s surprisingly funny.

The Good Lord Bird—book and show—is narrated by a fictional character not found in the historical record: Henry Shackleford, an enslaved child Brown quasi-adopts after his father dies. Brown mistakes Henry, who’s played in the series by Joshua Caleb Johnson, for a girl; seeing no reason to correct the mad-looking white man, Henry becomes “Henrietta.” He dons a dress and sticks by Brown’s side through the bloodiest months of Bleeding Kansas; goes north and eavesdrops on Brown’s meetings with Frederick Douglass (Daveed Diggs) and Harriet Tubman (Zainab Jah); and witnesses the planning, and botched execution, of the Harpers Ferry raid in October of 1859.

Henry Shackleford isn’t real, though he’s an extremely good literary device for a story that explores Brown’s fatherly tenderness and staunch commitment to interracial friendship. What other parts of the historical record does The Good Lord Bird twist, turn, and elide in telling its story?

That Bird

In the first episode, which follows the fighting between Brown’s band and pro-slavery forces in Kansas in the summer of 1856, Hawke’s John Brown gives Henry a feather from a “Good Lord Bird.” Brown’s son Frederick, who befriends the young Henry when he joins Brown and his group of guerrilla fighters, tells him that the birds are considered to be a source of enlightenment: “They say one feather from a Good Lord Bird will bring you understanding that would last your whole life.”

Ivory-billed woodpeckers were indeed called “Good Lord Bird” or “Great God Bird” because of their huge size and beautiful colors. The idea behind the nickname, just as Frederick explains on the show, is that people who spotted the gorgeous birds, which had a 2½-foot wingspan, couldn’t help but exclaim out loud. Ivory-billed woodpeckers have been thought extinct for more than half a century, although there have been several sightings reported (and debated) in the last 20 years.

Dutch Henry

When we meet the fictional Henry Shackleford and his father, they’re held in bondage by “Dutch” Henry Sherman, a German immigrant who has a tavern that (as Henry says in voice-over) “served as a post office, way station, rumor mill, and gin house for the Missouri Redshirts who came across the border to drink, throw cards, and holler about n****rs taking over the world.”

Though there’s no record of his enslaving a boy who ends up riding with John Brown, Dutch Henry Sherman had a store and tavern in Kansas much like the one Henry describes and, along with his two brothers, supported the pro-slavery cause. “By all accounts [the Shermans] were a brutal trio cut in the mold of border ruffians,” David S. Reynolds writes in his book John Brown, Abolitionist. Brown viewed the Shermans as enemies, and Dutch Henry’s brother William Sherman (“Dutch Bill”) was one of the five pro-slavery settlers killed by John Brown and his men in the course of the massacre at Pottawatomie Creek.

Brown’s Disguise

When Henry first meets John Brown in Dutch Henry’s tavern, the Old Man affects an Irish accent and introduces himself as “Shubel Morgan” (at least, until Dutch Henry asks for his name again, and Brown calls himself “Shubel Isaac,” then explaining “Isaac is my middle name”—again, this is a comedy). Brown did indeed use the alias “Shubel Morgan,” but that was a little later in his life, when he returned to Missouri in disguise in the winter of 1858, on a mission to free a group of enslaved people and bring them to Canada.

Brown’s Crew

John Brown’s men, says Henry in voice-over, were “a ragtag assortment of the scrawniest, saddest-looking individuals I ever saw. Bushwhackers, sticky-rope cattle rustlers, an Indian, even a Jew.” The show’s “Indian”—Ottawa Jones, played as a fierce and committed fighter by the actor Mo Brings Plenty—stays with Brown through the raid at Harpers Ferry.

The Good Lord Bird shows how fluid and diverse a crew Brown’s associates made. To Henry’s eyes, the group looks ragged, and Brown’s lack of discipline seems dangerous. (“He didn’t care much for the details of his army,” Henry says at another point. “Weren’t taking no attendance.”) But from our modern perspective, it’s remarkable how ecumenical Brown was in his alliances. The show’s “Jew” may be a reference to the historical figures Theodore Weiner, August Bondi, and Jacob Benjamin, three immigrants from Europe who joined with Brown in Kansas to fight for the Free State movement. And John Tecumseh “Ottawa” Jones was indeed an ally of Brown’s, although not present for the Harpers Ferry raid. Part Chippewa and part white, Jones was (as Reynolds writes) a “prosperous and well-educated” farmer, married to a white woman who came to the state as a missionary from Maine. The Joneses gave Free Stater forces material aid when Brown was in Kansas. Ottawa Jones suffered for it: Pro-slavery Missourians destroyed his farm in 1856.

But while Brown considered him a friend and a compatriot, Jones wasn’t one of the group that hid with Brown in the woods and fields in the summer of 1856, nor did he end up in the small band that fought with Brown at Harpers Ferry in October of 1859.

Animals

Did John Brown really, as The Good Lord Bird has it, keep a pet squirrel for 17 years? Did he wander the banks of a river, talking to a squirming captive rabbit about the Lord? That rabbit may be invention, but Brown was, overall, a lover of animals. Reynolds describes Brown’s childhood grief over the loss of a “bobtail squirrel” he had tamed. When Brown kept sheep during the earlier periods of his working life, Reynolds writes, he would stay up late at night when sickness hit, holding newborns to their ill mothers’ teats so that they wouldn’t starve.

Brown’s consideration for and kinship with animals was to become part of his legend. After seeing him speak in Concord, Massachusetts, in 1857, Ralph Waldo Emerson praised Brown in his journal, particularly mentioning the former shepherd’s closeness with animals and with nature: “He always makes friends with his horse or mule … and when he sleeps on his horse, as he does as readily as on his bed, his horse does not start or endanger him.”

The Killings

The first episode follows Brown and his band through the home invasion and killing of James Doyle, a pro-slavery settler whom Brown murders because he was present at Dutch Henry’s tavern and seemed to support the pro-slavery side. This part of the episode is a much slimmed-down version of the famous Pottawatomie massacre, in which John Brown, five Brown sons, and three others killed five pro-slavery settlers in the middle of the night of May 24, 1856.

On the show, the killings happen in part because Brown feels guilty that Henry’s father died at the hands of Dutch Henry Sherman. Brown decides to lead his men to the cabin looking for Sherman, to exact retribution. Because the show can’t feasibly include all the context of the political conflicts that led up to the Pottawatomie killings in real life, the murder of James Doyle feels more random, and much more shocking. The show’s Doyle, begging for his life, protests that he’s not truly pro-slavery, though he would like to own “some “n****rs” to work the land. In the historical record, Brown undertook the raid to make a point, after pro-slavery forces ravaged the Free State stronghold of Lawrence a few days before. And the real-life Doyle seems to have been much more active in pro-slavery activities than his fictional avatar protests.

Perhaps The Good Lord Bird chose to obscure some of this context for the raid so that the viewer would feel, as our audience avatar Henry does, deeply surprised by these events. This is probably also why Hawke’s Brown is much more intimately involved with the killing of James Doyle than the historical Brown. According to a later account from James Townsley, a Free Stater who was present on the night of the historical massacre, John Brown himself did not land the sword blows that killed four of the five men who died that night—though he did shoot James Doyle in the head. On the show, perhaps to heighten the shocking effect as Henry looks on, Hawke’s Brown kills Doyle with blows from his own sword; the sounds of metal cleaving flesh are obscenely loud.

His Last Words

The Good Lord Bird opens with Brown climbing a scaffold and, right before the hangman puts a hood over his head, saying, “What a beautiful country.” (He uses this phrase again, later in the episode, while burying his son Frederick.) Here, the show has compressed the time frame and edited reality a bit. Brown was said to have observed to those transporting him to the gallows: “This is a beautiful country. I never had the pleasure of seeing it before.” The Good Lord Bird’s choice to open the show with the slightly truncated version emphasizes the Old Man’s undaunted patriotism, even in the face of death.

"bird" - Google News

October 05, 2020 at 08:00AM

https://ift.tt/30yj2DY

Good Lord Bird historical accuracy: Fact vs. fiction in the Showtime series of James McBride's novel. - Slate

"bird" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2s1zYEq

https://ift.tt/3dbExxU

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Good Lord Bird historical accuracy: Fact vs. fiction in the Showtime series of James McBride's novel. - Slate"

Post a Comment