Millions of migratory birds fly south each year to winter in California, or continue beyond.

The white-faced ibis is one of the first. The large wading bird with its distinctive curved bill, like its avian counterparts that fill the sky in late summer and fall, relies on the state’s wetlands to rest and recharge.

But this year, the ibis that arrived at the California-Oregon border from points north didn’t find the marshes and ponds they’re accustomed to, just dust and dried-up mud. So the birds touched down only briefly and kept flying — some all the way to Mexico, said John Vradenburg, supervisory biologist for the Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex.

As California’s fall migration revs up, many birds will have to abandon familiar stops and make adjustments, often big ones, if they haven’t already, to adapt to a landscape stricken by drought. For some, the changes may be asking too much, and the coming months will be difficult.

“A lot of the birds are just bypassing the mid-continent and going straight to the Central Valley, but there’s not a lot of habitat to support them there either,” Vradenburg said. “Wetland availability is just really low (everywhere) right now. … This landscape (level) drying is a phenomenon we haven’t really seen probably since the 1930s, the Dust Bowl.”

An egret takes flight along the driving tour road on Saturday at the Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge in Willows. As California’s drought intensifies, migratory birds like egrets may struggle to the water and moist feeding grounds they need.

Chris Kaufman, Freelance / Special to the ChronicleThe fear is that migratory birds, from ibis and egrets to ducks and geese to hawks and eagles, won’t find the water and moist feeding grounds they need, even by flying the long distances they’re built for. Or, they’ll fly so far that they may tire, increasing risk of starvation, susceptibility to disease, vulnerability to predators and chance of reproductive failure — risks that grow as the stress continues over years.

Already, last year’s counts of traveling birds at popular stopovers and wintering areas in California were down. With the drought in its third year, marking the state’s driest three-year period on record and following a severe five-year drought last decade, scientists, environmental groups and hunting organizations say the slide could worsen.

“In a lot of ways, the (birds) are built to handle drought,” said Jeff McCreary, western director of operations for the conservation and hunting advocacy group Ducks Unlimited, which recently launched aerial surveys to figure out where waterfowl are going when there’s no water at their usual roosts. “If the drought continues years on end, though, it will start to outpace the ability of the birds to respond.”

* * *

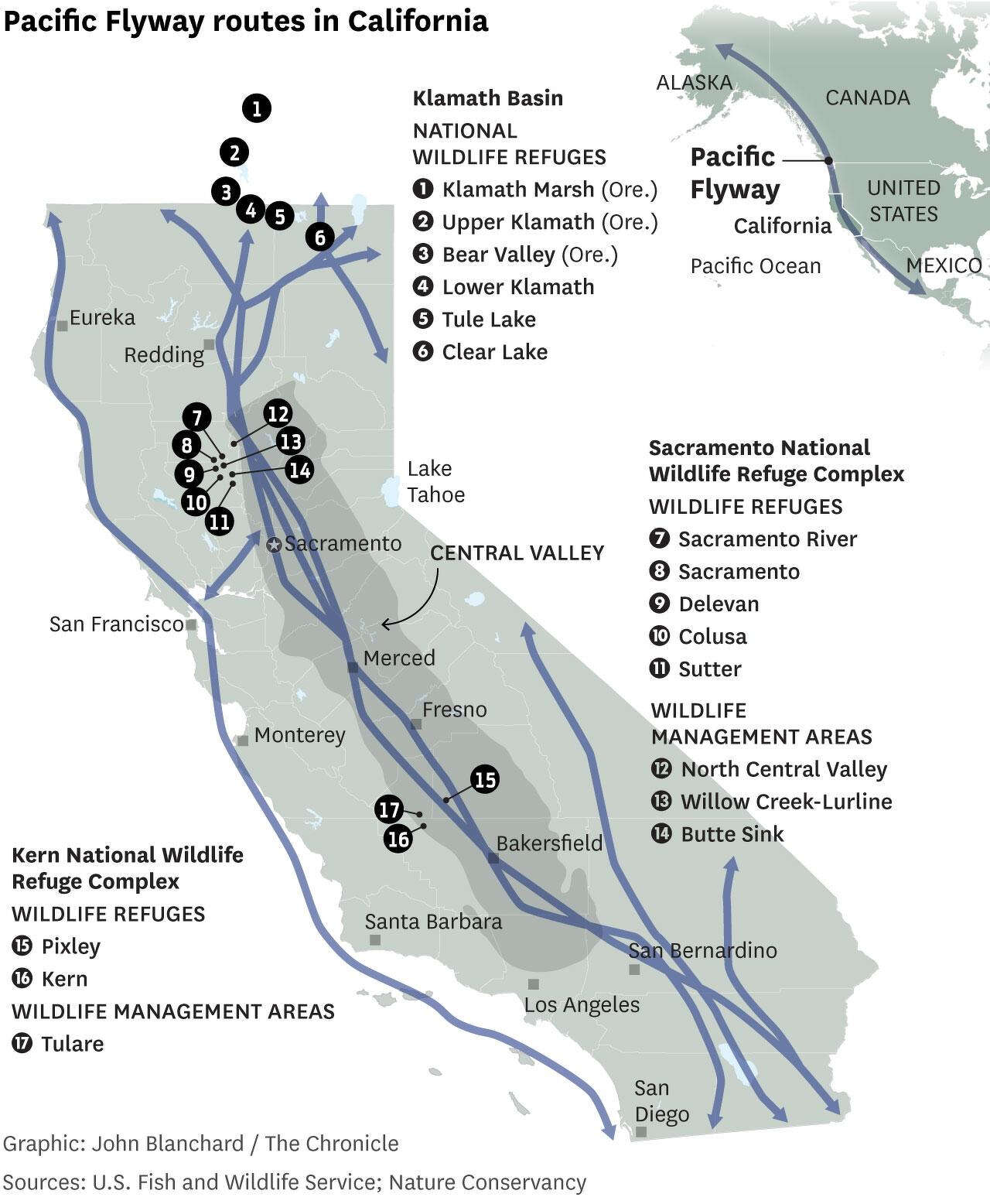

California is a key link in the 4,000-mile Pacific Flyway, one of the primary migratory routes used by birds to move north and south across the continent.

The fall flights, which sometimes originate as far north as eastern Russia and span as far south as Patagonia, demand spots across the nearly 800-mile-long state for birds to stop and refuel, with water, plants, insects and fish.

With 90% of California’s historic wetlands no longer around, the options for stopovers are limited, with several of the go-to points being refuges created by the state and federal government with support from environmental and hunting groups. Many are perilously low on food and water.

“Every year that we have drought, the problems in the flyway get magnified,” said John Carlson, president of the California Waterfowl Association. “The birds are resilient and they can move to where there’s water, but this is going to be a tough year.”

Some state and federal wildlife refuges have taken the unprecedented step of shutting down hunts for waterfowl in fall and winter, or delaying the season, because of the dry conditions and challenges for birds. Human predators would only add stress.

The Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge Complex is one that’s taken precautions, postponing its opener and reducing hunting quotas in many areas. The collection of five refuges in the Sacramento Valley has recently seen an influx of birds that are usually farther north this time of year, an advance that refuge managers chalk up to the feverish search for water.

The white-bodied, loud-honking snow geese have recently been reported in unusually high numbers, coming from Russia’s Wrangel Island and the western Arctic. So have greater white-fronted geese and northern pintails from Alaska. Most are holing up on the wetter east side of the Sacramento Valley.

The problem, refuge managers say, is that the parched landscape won’t sustain big numbers.

“These birds would typically be up in the Klamath Basin,” said Michael Derrico, supervisory biologist for Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge Complex. “There’s more pressure now on the food resources in the Central Valley.”

It’s the same story farther south in the Kern National Wildlife Refuge Complex, known for the sandhill cranes that come from Homer, Alaska, to winter in the San Joaquin Valley. Already, thousands of the once nearly extinct birds have arrived.

“We have more birds showing up and earlier, but we’re only able to provide so much,” said Miguel Jimenez, manager of the complex. “There’s just not enough habitat for us to support all the birds.”

Complicating matters, refuges face the same problems that many cities and farms confront during dry times: not having priority claims on water.

The Kern Refuge Complex, which relies on water releases from the federally operated Central Valley Project, received less than half of its full water allocation this year while the Sacramento Refuge Complex, also reliant on the federal project, received only slightly more. The Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex farther north is not allocated any water from the federal Klamath Project, and depends on excess in the system and from local farmers, of which there’s been little this year.

* * *

Beyond the refuges, many migratory birds seek out rice paddies, which serve as a surrogate for lost wetlands.

About 200 species of birds find shelter in the flooded fields and find food in what’s left of the harvest as well as in the insect- and crustacean-rich irrigation water. Some stay for days, like the recently arrived long-billed dowitcher. Others stay all winter long, like the incoming American wigeons and green-winged teals.

This year, however, less than half of the usual 520,000 acres of rice was planted in the Sacramento Valley because of water shortages, according to the California Rice Commission. This means less than half as much accommodation for birds.

“You take rice out of the equation, the Pacific Flyway will look a lot different — and not in a good way,” said Luke Matthews, wildlife programs manager for the commission. “The lack of food and the lack of habitat is going to leave birds with worse body condition. They’re not going to be as healthy.”

A dry wetlands area is seen on Oct. 22, at the Colusa National Wildlife Refuge in Colusa County

Chris Kaufman, Freelance / Special to the ChronicleIn an effort to preserve these watery areas for birds, the state and federal governments are paying millions of dollars to rice farmers to continue flooding their fields. Tens of thousands of additional acres are coming online, which Matthews called a “Band-Aid” for the migration, but one that’s essential for the moment.

An added concern with sparse water in the fields and wetlands is avian botulism. The bacterial disease can paralyze waterfowl and is common when bird concentrations are high and water levels are low.

“Once the birds get here in full force and they’re forced to stack together in the limited habitat, you have the potential for an outbreak that could be pretty devastating,” Matthews said. “It might even be better to have no water than a little water.”

An outbreak of botulism two years ago in the Klamath Basin, as the area began to dry up, killed more than 60,000 birds.

Avian flu is also a threat. This year’s strain of the virus, which has been detected in waterfowl in California, is being compared to one in 2015, which killed millions of domestic birds in the United States. Many chickens and turkeys were purposely put down to prevent spread of the disease, which moves readily between birds, including wild and domestic populations.

* * *

Nowhere is there more concern about birds than along the California-Oregon border.

The two most important refuges at the vast Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex — Tule Lake and Lower Klamath — have run dry, turning the areas into little more than mud flats. The Lower Klamath refuge has seen this before, but not since the 1940s.

Historically, this network of marshes and lakes, sometimes dubbed the “Everglades of the West,” has been visited by as many as 80% of the birds in the Pacific Flyway, leading refuge managers to call its decline this year the “collapse of the most important staging area” on the route.

Already, migratory waterfowl numbers at Tule Lake and Lower Klamath refuges fell 61% last year, compared with the prior year, according to refuge surveys. The estimated 42,716 birds that visited the refuges at peak migration last fall was the lowest count ever — and just 3% of what the peak was four years earlier.

“We’re seeing birds (this fall) but we’re not seeing them in any significant number,” said Vradenburg, the supervisory biologist at the complex.

Birds are silhouetted at dusk on Oct. 22 at the Colusa National Wildlife Refuge in Colusa County.

Chris Kaufman, Freelance / Special to the ChronicleWhen the ibis weren’t showing up in their usual droves, Vradenburg knew this year was going to be bad. Huge flocks of the birds from the Pacific Northwest and sometimes southern Canada have historically marked the beginning of the migration season.

“Most mornings in the summer (in the past), I would see two- or three-thousand birds fly over my house,” he said. “This year, I’d see maybe 10 or 15.”

While it’s too early to know how many migratory birds will end up visiting the Klamath Basin this fall, or any of the main spots in California, a recent state survey of breeding waterfowl shows that this segment of the population is slipping, meaning broader declines are almost inevitable.

In the state’s April survey, ducks, the majority of birds in the count, experienced a 19% decrease since 2019, the last year the census was done because of the pandemic. The number of American coots, the next most common bird, was down 30%.

“Birds have been through this before,” said Melanie Weaver, a senior environmental scientist with the state Department of Fish and Wildlife and a waterfowl expert who co-authored the April bird survey. “Drought is wired into waterfowl. They’re not going to fall out of the sky.

“That said,” she added, “we don’t want to see (dry conditions) every year, because it will cause a population decline.”

Kurtis Alexander is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: kalexander@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @kurtisalexander

"bird" - Google News

October 26, 2022 at 01:00AM

https://ift.tt/KMwDQBT

California drought: Migration of millions of birds being upended - San Francisco Chronicle

"bird" - Google News

https://ift.tt/fKjvhmX

https://ift.tt/z8ewkOL

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "California drought: Migration of millions of birds being upended - San Francisco Chronicle"

Post a Comment